by | Jan 11, 2017 | Advice, Blog

The advice in this post is just so marvellous I have just purchased her book on story structure and the accompanying workbook. Ms Weiland offers succinct advice not only on what to avoid, as well as why to avoid it and what it does to your narrative. I honestly could not have put it better. Rather than rehash the whole article I will summarise her main points, add my own input and examples, and link back to the original at the bottom.

Shall we begin?

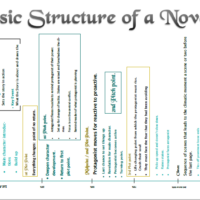

The breadth of description required of written prose is vast in comparison with visual media. However, the author is both guide and gatekeeper to the narrative description, deciding what the reader needs to know and when. Authors are also human and, as such, we like to play with the details and show off. This is true whether we write for fun or publication. The fact remains that if we wish our writing to improve there are four habits we must consciously learn to avoid.

- Looking too deeply at the relationships between minor characters. However close the attachment, or tense the conflict, the relationship between the minor players need not get a mention unless it has an effect on the plot. if you want to explore it further you can always take a leaf out of the likes of Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Shadow) or Anne McCaffrey (Nerilka’s Story) who have written whole versions of their works from the perspective of minor characters

- Travelling filler and uneventful journeys. Don’t try to stage direct an empty theatre: you’ll bore yourself as well as your audience.

- Repetition of conversations already witnessed. Say you were at a party, but one of the guests was reciting back to you a discussion you had already heard. You’d get bored pretty quickly right? So will your readers.

- Information-dumping. If you have found out something really interesting, and you just have to share it, use an end note (not the same as a footnote). It’s what they’re for. This way, you can still demonstrate the level of research you have put into your book, but you don’t have to break your narrative, and the reader gets a choice whether to read the proffered information or not.

Unnecessary scenes damage your story in several ways.

- They bore readers. Just like the way an advert break during really good film right before the climax could put off a viewer and make them change the channel, an info-dump or disjointed tangent will make them simply put the book down. Worse? It could make them avoid your other or future titles.

- Misdirection for dramatic effect. Don’t be the taxi driver who goes the long way around just because they want a bigger fare (we’ve all met at least one). Your reader is your passenger. They don’t need to know what the field they are passing looks like, or what people are doing at the side of the road unless it has something important to do with the story (disposing of what could be a body?). Deliberate red herrings are an old fashioned, cliched device and have very much gone out of fashion.

- Derail narrative. On the theme of minor-character relationship-overshare: narrative prose is not the same as a TV program where all speaking-character relationships must be visible and clear from the off. Unless the feelings your main character has towards the ever so dishy, leather clad pirate (Once Upon a Time) have a bearing on the direction of the plot (they get there eventually), they need to be left out. In Speaker for the Dead, Novinha’s love for Libo (who does not take an active role and appears mostly in reference) causes her to lock her files and hide the results of her experiments for fear that he would make the same discovery that had cost his father’s life. In this case, withholding that information did not have the desired effect, but the story would not have made sense without it. However, it could have easily been overdone, and I have seen it overdone time and time again (*cough*, Sword of Truth Series, *cough*)

- Fragment the story and distract your reader. If a scene does not fit, it can wreck the whole cohesion of the book. Keeping unnecessary scenes is like trying to add extra pieces to an already completed jigsaw puzzle just because you happen to like the colour contrast. Not only to they not add anything substantial to the picture as a whole, but they can detract from, hide, or even break up the other pieces.

Here is how to avoid these errors.

Plotter or not, once you have completed your first draft (not before) you will have to go through your novel from the perspective of a reader, but before you delete anything, save your book under a different name (2nd draft?), that way if you want to recover something you have previously deleted and paste it in a later part of the book, you will be able to.

- Mentally delete them. One by one, go through and look at every scene. Can your story survive without it, in regard to character development or plot cohesion? If so, delete it. You don’t need it.

- Sweep for opportunity-darlings. Those little nuggets of ‘narrative genius’ that occurred to you as you wrote but somehow slipped past your mental outline-guards? Get rid of them. If your story can survive without them, in regard to the criteria in the previous step, then they are gatecrashing your party, abusing the free bar, and need to be thrown out. Hint: they’ll be more common in the messy middle.

- Good use of scene structure. Here, I refer you to Ms Weiland’s guide to scene and sequel construction which can be found by following the link below. You’ll also find the Amazon.com link to her book.

Source:

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 40: Unnecessary Scenes – Helping Writers Become Authors

by | Nov 24, 2016 | Blog, Courses

Rayne Hall, for those not familiar with her, is a horror writer but she also writes some very helpful writing-guides. The subjects of these vary between marketing ideas, advice on how to write specific scenes, and how to self-edit (all very helpful to new writers or those who fancy a change of genre). You’ll still need an editor. Even editors use editors.

Now she is offering a free workbook when you sign up to the mailing-list. Be aware that it might take a day to come through so make sure you have the email address (from the confirmation) on your safe-senders list or it will end up in the junk file.

What is it?

This is a twenty-six-page collection of fifteen individual writing exercises, aimed to develop your own voice within your existing work. These exercises are very helpful and will aid you in your self-editing process. By all means allow your favourite authors to influence your work, there is even an exercise to pick your top five (harder than you think to narrow down: I came up with ten on the spot), but the idea is to emulate, not imitate. This will be a great help to new writers, and those who want to improve their work.

by | Sep 29, 2016 | Blog

Introduction

I should distinguish first, the differences between the roles of the editor and copy editor. It might seem at first, particularly to new writers, that the two roles are one and the same, but they vary definitively. There is no strict definition of who does what, which can lead to confusion over what to expect so it is vital for you to be sure exactly who offers what, and at what level so you can be sure that your book gets the right process. These service levels are dealt with in more details later in the post. Briefly, an editor is the second pair of eyes who will be able to look at an author’s manuscript objectively, and dispassionately, and thereby identify where the work has potential, where it falls down, and advise where changes are needed in order to make the work as good as it can possibly be (Oliver, 2003, p. 127) this will take several drafts.

While the use of the terms ‘editor’ and ‘publisher’ also appears to be inter changeable, particularly in writer’s guides written in the US, they also vary. In the US, the publisher is the printer. They prepare the material for printing, then issue the books, newspapers and magazines for sale to the readers. In the UK, the publisher is a person or company who is in the business of publishing printed material.

Self-editing is another different process, which will be covered in a different post. This is the furthest you can take your work without professional assistance. It is good practice to go through your own self editing process and take pains to get your work as close to being finished as possible before submitting any of your work to an editor. It will save you a great deal of time, money, and disappointment (Maitland, 2005, pp. 174-195). Finally, no type of editing service includes changing huge chunks of your work. Ghost writing and co-authorship are entirely different agreements, which have no bearing on the editorial process. These arrangements, for good reason, should be entered into separately.

What they will do.

‘An author’s publisher is, in effect, his/her very first, critical, perhaps over-critical, reader. If something strikes your publisher (who is on your side) as not very good, then it may have the same effect on other readers – the buying public, who are not on your side until your book persuades them that they should be.’ – Reay Tannahill (Oliver, 2003, p. 128)

Before work begins

The website Preditors and Editors, contains a list of editing services, which they rate according to their quality (Preditors & Editors, Inc., n.d.). A ‘not recommended’ rating is issued to services which fulfil one or more of several criteria. A good editor will only invoice you for work you have agreed for them to carry out. Here lies the importance of a fair service agreement, signed by both parties which should lay down the precise remit of the editor. This contract is an agreement between author an editor to perform a specific task or process. A good editor will acknowledge that it will take at least four rounds of editing before a work can be in anyway considered finished and ready to publish. A good editor will not make rash promises, in order to pull you in. A good editor will stick to their contract and deadlines: they want repeat business and to do this they will offer a good service – not low prices – and produce a good result,

Free sample editing

Sample edits allow an editor to demonstrate their ability to edit your work and provide an example to you of the standard you can expect from them. One page is reasonable to ask, and many offer this as standard practice, but you should not expect them to sample more than five pages. Remember that whilst they are trying to sell their services, their time and skills are as valuable as your own. At this is the stage an editor can also gain a rough impression of what level of service your work needs and how long it will take (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

Editing plan

This will detail the exact processes your work will undergo. It normally consists of four or five stages over many drafts. These exact processes and the wording of the plan will vary between services but this plan outlines the level of service which will be agreed to in your service contract. This should be produced prior to signing any agreement. A good editor will set realistic and fair deadlines in their contracts and they will stick to them. Be aware that sometimes work may take longer than previously estimated. A ten percent margin of error in this respect is not unreasonable and a fair service agreement will allow for this.

Service Agreement

No full manuscript should be submitted before a service agreement, which reflects what you have already agreed to has been signed by both you and the editor. This contract is an agreement formalises your agreement. If you are not entirely happy with the terms of an agreement, a good editor will negotiate before producing a contract. If they will not negotiate, do not sign anything. It should detail the agreed prices, the service levels and terminology, and the cancellation process.

The actual editing

Most importantly, it is not the job of an editor to research for, or to rewrite your work for you. An editor will suggest changes that they believe will improve the manuscript (Tuttle, 2005, p. 109). These may be minor corrections such as word misuse, or alerting you to the repetition of phrasing. They may also be major, such as removal of sections or even whole sub-plot lines, or including additional content. These changes are not compulsory. It is your work and you do not have to change anything unless you are entirely convinced (Tuttle, 2005, p. 109). That said, editorial advice should be given proper consideration, and not simply rejected if you find their reactions overly harsh. Editors can bring an unbiased eye to your work, as well as a totally candid assessment, whereas a friend or family member might be reluctant to point out any failings, lest it hurt your feelings.

A good edit consists of four distinct stages (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

-

Developmental, (structural or substantive).

Here an editor will look at how the story comes together and makes a note of trouble spots: where the plot is lost or inconsistent; where there is an excess of description; where the characters are indistinct. From this point, they will look at how sections might be reordered so they fit together better, and represent the expectations of the reader. This can be an expensive service if the whole of a manuscript needs restructuring so it is a good idea to address this issue before you start writing with a detailed outline. This can also be sent to an editor, together with your manuscript, but bear in mind that this may incur an extra cost (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

2. Paragraph Level (stylistic or line editing).

This stage resolves issues over the clarity and flow of your sentences. It could involve moving the sentences around to clear up the meaning, but it always aims to preserve your voice in your work (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014). If your sentences feel formulaic, with excess adjectives, the vocabulary is unsuitable for your audience (strong language etc.), you have used specialised jargon without taking the time to define terms, or your transition between paragraphs is disjointed, it might be a good idea to request a stylistic edit (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

3. Sentence Level (copy-editing).

After the editor has suggested the required changes to the content, with regard to accuracy and structure, the copy- editor (which may be the same person) will check the fine details such as spelling punctuation and grammar (Maitland, 2005, p. 174). This assess the grammatical structure of your sentences, ensuring the correct use of words and the consistency of argument or story line. The writer may have deviated from the expected course, due in part to the sheer number of small details they are trying to incorporate into a single narrative. Inconsistency in spelling can also be caught and picked up in sentence level editing so the author can be alerted and they can correct it in the next draft (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014). A good copy-editor will make sure a writer sees these corrections. This is easy to do in applications such as Word as it has a designated function to track changes. While you are under no obligation to accept them (Oliver, 2003, p. 128), it is recommended that your follow their advice.

4. Word Level (Proofreading)

This is the final stage, not the first. This is applied only after the structural issues have been addressed and resolved. It’s the final spit and polish. Typing, spelling and formatting problems are highlighted and an editor will examine how your text presents itself in both hard, and electronic formats. This is the final opportunity to catch errors before your work is laid before the public, for a reader to immediately point them out. (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

What they won’t do.

‘An average manuscript from a new author does need quite a large amount of editing, often two or three sets of revisions need to be carried out’ – Luigi Bonomi (Oliver, 2003, p. 127)

A good editor understands that editing can only do so much. As demonstrated above, it is their job to guide the author through a final process in regard to structure and storyline. In short:

- They will not rewrite your work. Nor will they promise to make your manuscript ready to publish within the first round of editing.

- They will not make any promises to get your work on best-seller lists.

- Beware of those who do make bold promises. You absolutely do not want to do business with those people.

- They will not make any attempts hard-sell any long term deals, or push you toward particular printers or publishers.

- If you are cold-called by an editor, do not use them. All contact should be initiated by you.

- A good editor will not use your work without your consent. They have no propriety rights to your work (unless they have bought the work from you, as in the case of traditional publishing). Submitting work to them for editing, does not imply that they have any permission to use it. Even with permission, they have to correctly attribute it to you. If an editor uses work by the writer (in whole or part) without permission, without attribution, this constitutes an abuse of fair use.

Bibliography

- Card, O. S., 1990. How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books.

- Koch Macleod, C. & Douglas, C., 2014. 4 Levels of Editing Explained: Which Service Does Your Book Need?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.thebookdesigner.com/2014/04/4-levels-of-editing-explained-which-service-does-your-book-need/

[Accessed 29 September 2016].

- Maitland, S., 2005. The Writer’s Way. London: Capella.

- Oliver, M., 2003. Write and sell your novel. 3 ed. Oxford: Howtobooks.

- Preditors & Editors, Inc., n.d. Editing, Copywriting, Ghostwriting, Indexing, & Software. [Online]

Available at: http://pred-ed.com/peesla.ht

[Accessed 29 September 2016].

- Tuttle, L., 2005. Writing Fantasy and Science Fiction. 2 ed. London: A & C Black Publishers Limited.