by | Jun 6, 2017 | Blog

1. First draft.

This is your raw manuscript complete with typos, grammar issues. I’m assuming here that you have already outlined by this point. If you haven’t don’t worry… yet. Suffice to say, this is not the version you want to send out to anybody especially not editors. Trust me, they will not thank you for making them read this. Sending the first draft to an editor could prove extremely expensive and time-consuming, not to mention disappointing when you see how much work still has to be done.

2. Self-edit

DO NOT SKIP THIS PART.

If you have an outline already, well done. If you don’t, pay attention. You need to outline the text as it is. Once you have done this you can compare it to your previous outline and see where you have strayed or dithered from your plan. It will also show you where you can improve. Once you have applied these changes, and cannot take it further, (and run a basic spell check) then is the time to submit to an editor.

3. Alpha readers and developmental edit.

By now you should have selected a few people to give your manuscript an initial once over. Doing this and submitting the manuscript to an editor will provide reader perspective at the same time and will allow you to gauge the readability sooner rather than later. Some might find your style a little too formal for the genre, others too casual. Inappropriate tone can have a dire impact on the reception your work receives and at this stage you have time to fix it.

The developmental edit looks at your plot as a whole and guides you in how to correct it. Listen to your editor. This is not the stage to be worrying about spelling and grammar and most will not bother with it. There is no point correcting that side of things until the story is right.

Apply changes.

It is up to you to decide how you apply the advice. It’s your manuscript, just bear in mind that your editor wants your book to do as well as you do. Their job is to help you improve upon what you have, not to tell you how good it already is. Nor is it their job to write the story for you.

4. Copyedit

DO NOT MISTAKE THIS FOR THE PREVIOUS STAGE.

Copy editing is where the grammar and sentence structure is adjusted for clarity, and punctuation has been checked. It is a little more involved than proofreading but all structural issues should already have been addressed. Copy editing is very different from developmental editing. If your copyeditor is finding problems with plot, dialogue flow and characters it implies one (or more) of the following.

-

You have involved them too early. This is the most common and mostly occurs because of a fundamental misunderstanding about copyediting involves. You might be able to renegotiate the agreement from copy edit to developmental edit but bear in mind that this might well cost you more than the lower level edit. Not all editors offer higher and lower level editing, but they may be able to point you at a reliable source if they don’t.

-

You have not listened to your editor. A competent copy editor should let you know as soon as they realise that your text is not ready for them and advise you on how to go forward. When they have alerted you to the problems, go back to the notes from your developmental editor and apply the relevant changes. A good copyeditor will NOT try to get more money out of you. Nor will they offer to do both levels in one go. If you ask, they should politely decline and tell you why.

If your manuscript is less than 10k words they might continue the work and let you know of the holes. If it is more they should pause and consult you as to the direction they should take. It is important that you respond promptly to this as it could impact on your schedule if you do not. If you want them to continue working on your manuscript is it up to you to ask them and for you to ask how much more it will cost. Do not simply assume they will do it at the same rate. The SfEP recommended minimum rate for developmental editing is £30.50 per hour. For copyediting, the recommended rate is £26.50. this is because one level is more detailed and involved than the other.

-

Both.

5. Proofread.

Once you have applied the changes you will need a proofreader to go over the manuscript in detail to filter out any errors that have crept in during the last stage. Intervention here should be minimal. If your copy editor has done their job properly, nothing beyond spelling and punctuation should need to be corrected.

This is the last stage of editing. For those of you who don’t know, it gets its name from the phrase ‘galley proof’ which would be the final copy presented to the typesetter prior to printing. It’s really the last chance to correct typos and other little errors.

6. Write blurb.

By this stage you should have had a final plot in place for some time. I found that the outline I created in the self-edit helped me to write mine as it offered a readymade summary of the whole. These are not easy to write. You have spent months working on this, so how do you summarise your work into a single paragraph? There are services which will help you do this, but it might be worth asking your developmental editor for a hand. This is your elevator pitch for your story so it is worth taking the time to get it right.

7. Cover art.

Unless you are a cover designer, do not try to do this yourself. Dabbling in watercolours is not the same as being able to create a dynamic, eye-catching cover that competes with all the other covers AND reflects your book. You need to be clear about the sort of thing you need. Your designer is not a mind reader.

8. Formatting.

A minefield of technical tripwires. If you have done it before, go for it. Otherwise, use something like Vellum and get it right. I’ve not used it myself but I have heard a lot of positive things about its usability and results. The problem here is that Vellum is a MAC only piece of software and not all of us have MAC money. You can’t go wrong with the practice of finding someone who knows what they are doing and paying them for their time and effort.

9. Send out to trusted beta readers

WHO SHOULD NOT BE PICKING UP ERRORS BY THIS STAGE

The beta reading stage is a reader feedback stage only. They should not be finding errors or typos, they should not be finding plot holes or inconsistencies. The copy they read should be as near to being published as possible. Relying on readers (often unpaid) to do the job of a developmental editor is not only unwise but unfair to your readers

Finding reliable readers might be difficult to manage but writers’ critique groups might be a good place to start looking. Some betas might go quiet for no apparent reason, others might not finish the book at all. Don’t worry. Find another and remember not to approach that person in the future. This is why it is important that you select five or six people to read who can be relied upon to come back to you with valuable feedback. If you use one who charges, be sure to ask for references that you can check if you have never encountered them before. You don’t want to end up paying, only for them to disappear.

10. Publish.

This is up to you. Also, this post is not about the relative pros and cons of self vs. traditional publishing. The most important piece of advice I can offer here is that you should not be paying the publisher to print your work. They should be buying it from you. Whenever a publisher starts asking for you to pay them, walk away.

11. Give your team feedback

When you sent your work to alpha readers for a sample response you did so to gauge how it was received, so you knew how to improve upon it. The same applies to other creative industries. They are not looking for an essay on their services, just a thank you for their time and some pointers on what they did well and how they can improve. Whether editors, cover artists, formatters or readers, it is vital that you offer them feedback. They don’t know how they’ve done unless you tell them, and a good review, or recommendation or two doesn’t go amiss either. These days, simply paying the invoice and disappearing is not sufficient to let people know they have done the job well. Failure to offer feedback can often be taken as a negative response to their work.

by | Sep 29, 2016 | Blog

Introduction

I should distinguish first, the differences between the roles of the editor and copy editor. It might seem at first, particularly to new writers, that the two roles are one and the same, but they vary definitively. There is no strict definition of who does what, which can lead to confusion over what to expect so it is vital for you to be sure exactly who offers what, and at what level so you can be sure that your book gets the right process. These service levels are dealt with in more details later in the post. Briefly, an editor is the second pair of eyes who will be able to look at an author’s manuscript objectively, and dispassionately, and thereby identify where the work has potential, where it falls down, and advise where changes are needed in order to make the work as good as it can possibly be (Oliver, 2003, p. 127) this will take several drafts.

While the use of the terms ‘editor’ and ‘publisher’ also appears to be inter changeable, particularly in writer’s guides written in the US, they also vary. In the US, the publisher is the printer. They prepare the material for printing, then issue the books, newspapers and magazines for sale to the readers. In the UK, the publisher is a person or company who is in the business of publishing printed material.

Self-editing is another different process, which will be covered in a different post. This is the furthest you can take your work without professional assistance. It is good practice to go through your own self editing process and take pains to get your work as close to being finished as possible before submitting any of your work to an editor. It will save you a great deal of time, money, and disappointment (Maitland, 2005, pp. 174-195). Finally, no type of editing service includes changing huge chunks of your work. Ghost writing and co-authorship are entirely different agreements, which have no bearing on the editorial process. These arrangements, for good reason, should be entered into separately.

What they will do.

‘An author’s publisher is, in effect, his/her very first, critical, perhaps over-critical, reader. If something strikes your publisher (who is on your side) as not very good, then it may have the same effect on other readers – the buying public, who are not on your side until your book persuades them that they should be.’ – Reay Tannahill (Oliver, 2003, p. 128)

Before work begins

The website Preditors and Editors, contains a list of editing services, which they rate according to their quality (Preditors & Editors, Inc., n.d.). A ‘not recommended’ rating is issued to services which fulfil one or more of several criteria. A good editor will only invoice you for work you have agreed for them to carry out. Here lies the importance of a fair service agreement, signed by both parties which should lay down the precise remit of the editor. This contract is an agreement between author an editor to perform a specific task or process. A good editor will acknowledge that it will take at least four rounds of editing before a work can be in anyway considered finished and ready to publish. A good editor will not make rash promises, in order to pull you in. A good editor will stick to their contract and deadlines: they want repeat business and to do this they will offer a good service – not low prices – and produce a good result,

Free sample editing

Sample edits allow an editor to demonstrate their ability to edit your work and provide an example to you of the standard you can expect from them. One page is reasonable to ask, and many offer this as standard practice, but you should not expect them to sample more than five pages. Remember that whilst they are trying to sell their services, their time and skills are as valuable as your own. At this is the stage an editor can also gain a rough impression of what level of service your work needs and how long it will take (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

Editing plan

This will detail the exact processes your work will undergo. It normally consists of four or five stages over many drafts. These exact processes and the wording of the plan will vary between services but this plan outlines the level of service which will be agreed to in your service contract. This should be produced prior to signing any agreement. A good editor will set realistic and fair deadlines in their contracts and they will stick to them. Be aware that sometimes work may take longer than previously estimated. A ten percent margin of error in this respect is not unreasonable and a fair service agreement will allow for this.

Service Agreement

No full manuscript should be submitted before a service agreement, which reflects what you have already agreed to has been signed by both you and the editor. This contract is an agreement formalises your agreement. If you are not entirely happy with the terms of an agreement, a good editor will negotiate before producing a contract. If they will not negotiate, do not sign anything. It should detail the agreed prices, the service levels and terminology, and the cancellation process.

The actual editing

Most importantly, it is not the job of an editor to research for, or to rewrite your work for you. An editor will suggest changes that they believe will improve the manuscript (Tuttle, 2005, p. 109). These may be minor corrections such as word misuse, or alerting you to the repetition of phrasing. They may also be major, such as removal of sections or even whole sub-plot lines, or including additional content. These changes are not compulsory. It is your work and you do not have to change anything unless you are entirely convinced (Tuttle, 2005, p. 109). That said, editorial advice should be given proper consideration, and not simply rejected if you find their reactions overly harsh. Editors can bring an unbiased eye to your work, as well as a totally candid assessment, whereas a friend or family member might be reluctant to point out any failings, lest it hurt your feelings.

A good edit consists of four distinct stages (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

-

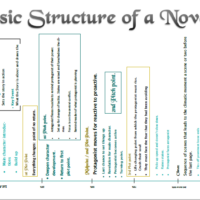

Developmental, (structural or substantive).

Here an editor will look at how the story comes together and makes a note of trouble spots: where the plot is lost or inconsistent; where there is an excess of description; where the characters are indistinct. From this point, they will look at how sections might be reordered so they fit together better, and represent the expectations of the reader. This can be an expensive service if the whole of a manuscript needs restructuring so it is a good idea to address this issue before you start writing with a detailed outline. This can also be sent to an editor, together with your manuscript, but bear in mind that this may incur an extra cost (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

2. Paragraph Level (stylistic or line editing).

This stage resolves issues over the clarity and flow of your sentences. It could involve moving the sentences around to clear up the meaning, but it always aims to preserve your voice in your work (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014). If your sentences feel formulaic, with excess adjectives, the vocabulary is unsuitable for your audience (strong language etc.), you have used specialised jargon without taking the time to define terms, or your transition between paragraphs is disjointed, it might be a good idea to request a stylistic edit (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

3. Sentence Level (copy-editing).

After the editor has suggested the required changes to the content, with regard to accuracy and structure, the copy- editor (which may be the same person) will check the fine details such as spelling punctuation and grammar (Maitland, 2005, p. 174). This assess the grammatical structure of your sentences, ensuring the correct use of words and the consistency of argument or story line. The writer may have deviated from the expected course, due in part to the sheer number of small details they are trying to incorporate into a single narrative. Inconsistency in spelling can also be caught and picked up in sentence level editing so the author can be alerted and they can correct it in the next draft (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014). A good copy-editor will make sure a writer sees these corrections. This is easy to do in applications such as Word as it has a designated function to track changes. While you are under no obligation to accept them (Oliver, 2003, p. 128), it is recommended that your follow their advice.

4. Word Level (Proofreading)

This is the final stage, not the first. This is applied only after the structural issues have been addressed and resolved. It’s the final spit and polish. Typing, spelling and formatting problems are highlighted and an editor will examine how your text presents itself in both hard, and electronic formats. This is the final opportunity to catch errors before your work is laid before the public, for a reader to immediately point them out. (Koch Macleod & Douglas, 2014).

What they won’t do.

‘An average manuscript from a new author does need quite a large amount of editing, often two or three sets of revisions need to be carried out’ – Luigi Bonomi (Oliver, 2003, p. 127)

A good editor understands that editing can only do so much. As demonstrated above, it is their job to guide the author through a final process in regard to structure and storyline. In short:

- They will not rewrite your work. Nor will they promise to make your manuscript ready to publish within the first round of editing.

- They will not make any promises to get your work on best-seller lists.

- Beware of those who do make bold promises. You absolutely do not want to do business with those people.

- They will not make any attempts hard-sell any long term deals, or push you toward particular printers or publishers.

- If you are cold-called by an editor, do not use them. All contact should be initiated by you.

- A good editor will not use your work without your consent. They have no propriety rights to your work (unless they have bought the work from you, as in the case of traditional publishing). Submitting work to them for editing, does not imply that they have any permission to use it. Even with permission, they have to correctly attribute it to you. If an editor uses work by the writer (in whole or part) without permission, without attribution, this constitutes an abuse of fair use.

Bibliography

- Card, O. S., 1990. How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books.

- Koch Macleod, C. & Douglas, C., 2014. 4 Levels of Editing Explained: Which Service Does Your Book Need?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.thebookdesigner.com/2014/04/4-levels-of-editing-explained-which-service-does-your-book-need/

[Accessed 29 September 2016].

- Maitland, S., 2005. The Writer’s Way. London: Capella.

- Oliver, M., 2003. Write and sell your novel. 3 ed. Oxford: Howtobooks.

- Preditors & Editors, Inc., n.d. Editing, Copywriting, Ghostwriting, Indexing, & Software. [Online]

Available at: http://pred-ed.com/peesla.ht

[Accessed 29 September 2016].

- Tuttle, L., 2005. Writing Fantasy and Science Fiction. 2 ed. London: A & C Black Publishers Limited.