by Anna Johnstone | Sep 25, 2017 | Advice, Service

A lot is said about how to find the right editor for you but today’s post is about being a good client. I had not intended for this to be this week’s post but given the circumstances, I thought this needed to be said.

Most of us know by now that the business relationship runs both ways. It should be one of mutual benefit and courtesy. Most of you know you need to be polite to editors when introducing your work, and they know to be tactful and treat your work with respect and discretion. Most of you know that most editors are very busy and cannot simply drop everything to make your work an immediate priority, but we still try to be polite when dealing with even the most ‘urgent’ projects. However, there are times when we meet those who don’t know these things, and today was one of them. I would like to draw from my own experience for an example of how not to introduce yourself to an editor. I will not name names. Doing so would be unprofessional and serve no purpose other than to exacerbate the problem, However, I do not feel that ignoring this experience will do any good either. For the moment there are two things authors need to remember;

- Good customer service does not mean being a doormat and accepting poor treatment just to get the client. Good customer service requires effort on behalf of the client too.

- Editors talk… A lot… About everything…

A few days ago I received an unsolicited ‘friend’ request from a member of one of the many writer’s groups I am a part of on Facebook. Recognising the name and thinking it’s about editing as it came on that profile, I accepted it and sent an invitation to my editor’s page to let them know it is there. This is not the same as a ‘request’ and people are free to decline it. I had thought nothing of it since given that my service has been closed for the last few days following the sudden death of my father. It strikes me that if he had really read my page he would have seen my pinned post. I digress…

Today I have experienced possibly the worst example of entitled behaviour since I started fourteen months ago. I arrived at my page to check my messages to find a personal message (not to the page, but to me personally) to say that they had liked my page and would I now like theirs “Only if deserved”. I didn’t get a chance to tell them that I was rather busy and would take a look when I had time because when I gently pointed out that my service page does not engage in like-swapping he began hounding me to just follow the link to his page and hit ‘like’ (even the most technologically naive of us should know not to ‘just follow’ any link.) just because he had liked mine. He had not used my service or put work my way so I am surprised he did. When I told him his behaviour to me was aggressive, he threw a tantrum that would have embarrassed Super Nanny; accusing me of spamming him, even though I explained that the invitation was only that; an invitation, and telling me not to buy his book. At no point did I say I would not like his Facebook page, but I was not given the opportunity to say that I would take a look when I had time because I was blocked before I could and simply because I would not drop everything and give him exactly what he wanted when he wanted it. He wanted me to like his page as an endorsement to his work without ever having read it.

In a way, I am sort of glad that this client has exposed his nature as a difficult client before I had to deal with him. This person is not the type of client this service is looking to engage with. Nor will it be. Ever. What did he do wrong, you ask? Firstly he assumed that he had an automatic right to my time and attention and that I should be grateful for his and jump to his will. It would take me time to go to his page and read his work. Time that I just don’t have this week. Yes, his primary introduction was fairly polite but his tone and demeanour changed to one of affronted aggression the moment things did not begin to happen exactly as he would like. That was his second mistake.

Remember, that editors are more than merely a living spell checker. We have lives and we have self-respect and we talk to each other. We know who the merely difficult clients are. We also know who the ones to avoid are. This is the beauty of being a freelancer. We have the privilege of choosing who we deal with. Imagine he had behaved that way to waiting for staff or someone at a call centre who did not have that option? It is not okay to treat anybody that way and if the cost of not putting up with it means one less rude or difficult client then that price is worth it.

by | Jan 18, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Last week I talked about unnecessary content and scenes which do not drive your story ahead. This week I am going to continue on that theme because I cannot stress enough the importance of clarity. While a good structure is vital, don’t be in too much of a hurry, or try to race through to the end. Writing is a hike, not a 100-yard dash. Hiking means being able to take in the surroundings, enjoy the autumn colours, spot wildlife, and properly stretch your creative legs. Doing it at a flat-out run means indistinct settings and unclear description. By trying to go too fast, you risk missing out details which help to set the scene. It will not make your reader more alert but lead them to ask the wrong questions about your narrative. In turn, being vague or indistinct means you are leading the readers’ attention away from what they need to know about the story, and missing out on an opportunity to build some depth into your characters through observation of their reactions.

Look at the following examples from K.Weiland’s ‘Most common Mistakes’ post from 2011:

- Maddock looked at the wall, which seemed to be smeared with spaghetti sauce.

- The bomb fell approximately ten or twelve feet away from me.

- Elle was about forty-five minutes late for her dentist appointment when a cop pulled her over, apparently for speeding.

- Mark’s figures revealed that the addition to the house would take up roughly fifty square feet.

Do any of them really help you to set the scene or give the reader a feeling that they need to know this? Nor me. It makes me think this is just filler. Why is the author wasting my time in telling me this? Take out the supposition and the approximation, then we know that the information is important and we will probably need to remember it later. Being unsure of the measurement of the house could prove very expensive, but being definite about it has us asking, why he wants to extend? Is Mark trying to hide something? Is he building a secret den? We know when something comes out flat. It feels trite or contrived; as if it could really be done away with. Being vague has the same effect. If that information is important then the ‘seemed to’, estimations, and approximations need to go. Your author voice will come through the stronger for it.

Sometimes, however, you will need to guide the reader or drop hints about the action or something the main character has observed. There are ways to do this but many of them are wrong. K. Weiland has again offered us a handy list of words to avoid:

- Seem

- Approximately

- About

- Appear

- Look as if

- Roughly

- More or less

- Give or take

- Almost

- Nearly

Persuasive, and evocative descriptions are a vital part of any narrative. Being vague is apologising to the reader for knowing more than they do, or trying to point something out and trying not to sound too clever about it. Stop apologising. Your job is to direct the gaze of your readers. Do not hesitate to give a full sensory experience. In a crime scene, for instance, your main character would be looking for clues. Your reader will be asking what did the air smell of (decay?) or was there a lot of blood or how far the deceased’s head had landed from their body (have someone use a tape measure). ‘Seemed to’ writing will only serve to diminish their experience, as well as rob at least two people of the experience of imagining it. This is not to say that you cannot use metaphor to transmit your meaning, but be cautious. There is the risk that you, as a new writer, will be tempted to hold your reader’s hand and explain them. Don’t. If you have got it right, the reader will understand it. Likewise, if you show your reader what is there, then they will see it.

Sweeping statements and generalisation is another form of dithering to look out for, and eliminate. You don’t need to make sure the reader ‘gets it’. Long winded justifications of your action won’t achieve this either. By going around the houses in order to set the scene you risk boring your audience with the minutiae and they will miss things they are meant to see. It also hints that you are unconvinced by your own story. The message here is to slow down. Be bold enough to say precisely what you mean and what you want your readers to see. Your readers will thank you for it.

Sources

by | Jan 11, 2017 | Advice, Blog

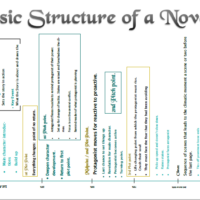

The advice in this post is just so marvellous I have just purchased her book on story structure and the accompanying workbook. Ms Weiland offers succinct advice not only on what to avoid, as well as why to avoid it and what it does to your narrative. I honestly could not have put it better. Rather than rehash the whole article I will summarise her main points, add my own input and examples, and link back to the original at the bottom.

Shall we begin?

The breadth of description required of written prose is vast in comparison with visual media. However, the author is both guide and gatekeeper to the narrative description, deciding what the reader needs to know and when. Authors are also human and, as such, we like to play with the details and show off. This is true whether we write for fun or publication. The fact remains that if we wish our writing to improve there are four habits we must consciously learn to avoid.

- Looking too deeply at the relationships between minor characters. However close the attachment, or tense the conflict, the relationship between the minor players need not get a mention unless it has an effect on the plot. if you want to explore it further you can always take a leaf out of the likes of Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Shadow) or Anne McCaffrey (Nerilka’s Story) who have written whole versions of their works from the perspective of minor characters

- Travelling filler and uneventful journeys. Don’t try to stage direct an empty theatre: you’ll bore yourself as well as your audience.

- Repetition of conversations already witnessed. Say you were at a party, but one of the guests was reciting back to you a discussion you had already heard. You’d get bored pretty quickly right? So will your readers.

- Information-dumping. If you have found out something really interesting, and you just have to share it, use an end note (not the same as a footnote). It’s what they’re for. This way, you can still demonstrate the level of research you have put into your book, but you don’t have to break your narrative, and the reader gets a choice whether to read the proffered information or not.

Unnecessary scenes damage your story in several ways.

- They bore readers. Just like the way an advert break during really good film right before the climax could put off a viewer and make them change the channel, an info-dump or disjointed tangent will make them simply put the book down. Worse? It could make them avoid your other or future titles.

- Misdirection for dramatic effect. Don’t be the taxi driver who goes the long way around just because they want a bigger fare (we’ve all met at least one). Your reader is your passenger. They don’t need to know what the field they are passing looks like, or what people are doing at the side of the road unless it has something important to do with the story (disposing of what could be a body?). Deliberate red herrings are an old fashioned, cliched device and have very much gone out of fashion.

- Derail narrative. On the theme of minor-character relationship-overshare: narrative prose is not the same as a TV program where all speaking-character relationships must be visible and clear from the off. Unless the feelings your main character has towards the ever so dishy, leather clad pirate (Once Upon a Time) have a bearing on the direction of the plot (they get there eventually), they need to be left out. In Speaker for the Dead, Novinha’s love for Libo (who does not take an active role and appears mostly in reference) causes her to lock her files and hide the results of her experiments for fear that he would make the same discovery that had cost his father’s life. In this case, withholding that information did not have the desired effect, but the story would not have made sense without it. However, it could have easily been overdone, and I have seen it overdone time and time again (*cough*, Sword of Truth Series, *cough*)

- Fragment the story and distract your reader. If a scene does not fit, it can wreck the whole cohesion of the book. Keeping unnecessary scenes is like trying to add extra pieces to an already completed jigsaw puzzle just because you happen to like the colour contrast. Not only to they not add anything substantial to the picture as a whole, but they can detract from, hide, or even break up the other pieces.

Here is how to avoid these errors.

Plotter or not, once you have completed your first draft (not before) you will have to go through your novel from the perspective of a reader, but before you delete anything, save your book under a different name (2nd draft?), that way if you want to recover something you have previously deleted and paste it in a later part of the book, you will be able to.

- Mentally delete them. One by one, go through and look at every scene. Can your story survive without it, in regard to character development or plot cohesion? If so, delete it. You don’t need it.

- Sweep for opportunity-darlings. Those little nuggets of ‘narrative genius’ that occurred to you as you wrote but somehow slipped past your mental outline-guards? Get rid of them. If your story can survive without them, in regard to the criteria in the previous step, then they are gatecrashing your party, abusing the free bar, and need to be thrown out. Hint: they’ll be more common in the messy middle.

- Good use of scene structure. Here, I refer you to Ms Weiland’s guide to scene and sequel construction which can be found by following the link below. You’ll also find the Amazon.com link to her book.

Source:

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 40: Unnecessary Scenes – Helping Writers Become Authors

by | Dec 7, 2016 | Blog

10 powerful tips on avoiding telling writing in creative writing.

“Creative writing teachers love to dole out wisdom or advice about fiction writing, as if they’re part of some esoteric order that guarantees enlightenment to all who memorize their pearls of wisdom. One of the most often quoted axioms is: “Show, don’t tell.” The idea is to keep students from explaining the story, that is, to stop them from using telling writing and get them to use showing writing instead.”

Source: Ten Tips to Help You Avoid Telling Writing | Scribendi.com

by | Dec 6, 2016 | Advice, Blog

Choosing an editor is not easy. The good ones have fees that could choke a horse. However, they are GOOD editors, so the fees they charge are worth it. If you can afford those fees. Unfortunately, many Indie authors just can’t break out that kind of cash.

Enter the rip off artists. They come in many levels of incompetence from authors who just want to make some side cash but don’t really know how to edit, to outright thieves who will take your money and give you nothing in return. Unfortunately, the latter kind thrives on the internet. We have all heard the stories of writers victimised by people calling themselves editors but didn’t even fix spelling mistakes, much less formatting, style, or continuity issues. As an editor myself, I am always learning and improving my craft this kind of thing makes me so angry – not least because it taints all freelance editors with the same reputation – but rest easy. This post is not an estate agent type post telling you to only trust me and ignore all those other editors. Finding the right editor for you is important.

So here are some guidelines for how to find the honest ones, pick an one, and dealing with them. Feel free to pipe up in the comments with any other suggestions I might have missed.

- Go with someone you know or who is recommended. If you can’t do that, the following steps can help.

- Do your research: collect reviews and referrals. How do they respond to complaints?

- Ask for a sample edit from the first chapter of your book, before any money changes hands. A new editor should be willing to do this to get your business, and most honest editors offer this as standard.

- Have someone you already trust and knows what they are doing, read the sample and let you know if they are good.

- Try to find one who will take a deposit up front and charges balance when the job is complete. If they demand the whole balance up front, steer clear. That said, I do expect full payment up front for small jobs (less than 10 pages =2500 words), but 50% of that is refundable if the client is not happy with my work

- Generally, I would advise you to avoid those who demand the full amount upfront. If their work is genuinely substandard –this is not the same as being unhappy about harsh feedback- do not pay the balance and demand your deposit back. New writers should be aware that it often takes several rounds of editing before your work is publishable.

- No editor can wave a magic wand and suddenly turn an unstructured first draft into a literary marvel in one go, and no reputable editor will claim to be able to. It depends entirely on the submitted work.

- Not all editors offer the same services or deal with the same type of text. You need to find out which genre they will work with and what levels they offer. I offer all four levels and am pretty much happy to edit whatever crosses my desk. Others may only deal with certain genres, or offer higher level editing. An honest editor will use your work to assess the level you are writing at and determine what the work needs. They will advise you what needs to be done, and if they are not able to offer the full scope of work required, you may find they will point you in the direction of someone who can.

- If you have ever dealt with an editor who has given you less than the quality of work promised for your money, you still have rights. A freelancer is subject to the same consumer laws as everyone else.

- You want to engage with someone who will cut deep and pick up the typos and mistakes. Remember, a good editor is on your side. A reader is not. The editor wants you to be able to publish your best work possible. You are not looking for ‘nice’. If they go too easy on you or appear to be in a rush to get to print, it can still count as bad editing. The reader will not be nice or give you the benefit of the doubt as it’s your first book. They will, at best, put your book down and never read your work again. At worst, they will leave a scathing review from wherever they bought it, and they will still never read your work again.

- A good editor will not point you at a publisher or insist that their services rely on you going with a particular press. If they do, they are probably taking a back-hander. I’m afraid you will have to do your homework for that too.