Outlining the obvious.

“Using the outline to figure out the technicalities of your plot gives you the freedom to deeply explore your characters, settings and themes in intimate detail in your first draft.”

– K. Weiland | Outlining your Novel: Map your Way to Success –

By using brief bullet lists to sketch out the order in which events in our story takes place provides a map. It doesn’t have to be laden with small details and contrary to popular belief, it doesn’t have to take as long as writing the book BUT a succinct outline will help identify and gaping holes in your plot and enable you to fix them before you start writing.

A rough outline will also allow you to regulate the pace of the story, set up the tone for the next chapter, and get a general idea of what fits with what, on a step-by-step basis. It keeps the story from drifting away from you and enables you to weave in a couple of complimentary sub-plots, making sure you use adequate foreshadowing for plot twists. My advice on sub-plots is to keep them to a minimum. Too many and you risk crowding- out the main plot. If you are going to use sub-plots, you need to be as consistent as with the main plot (beginning, middle, end) as you are with the main plot or you will leave your reader wondering what happened to characters who just seemed to vanish.

The length of an outline will vary between authors. It really is up tp you and there is no strict set of rules to follow when planning. Some will spend weeks planning every detail of their world. I am finding that I prefer to map out the direction of the story then fill in the details as I go. It gives me the best of both worlds. They don’t need formal formatting because that information is for you (Who else is going to see it?). It doesn’t mean anything is set in stone either. If you feel that something else will work better, then use that idea. It’s your work. K.Wieland looks on an outline as a barebones first-draft, and I tend to agree. It’s merely a frame, not a rune covered cairn stone which must be obeyed like you have made a pledge to Odin. It’s the ideal place to make your mistakes because here they are easily corrected, and invisible to the reader. You can lay down the foreshadowing of events and see at a glance if your chapters are missing anything before you even start writing.

What do I need?

A general rule of outlining is that there is no, one set of kit or right way to do it apart from the one that works for you. It is a trial and error process that only you will be able to find for yourself. You might even find that your preferred method just isn’t working for you and have to find another. Chapter 2 of K.Weiland’s Outlining Your Novel looks at some of the means of planning available to most writers, as well as the approaches. Like Ms Weiland, I prefer to take myself away from the screen and distractions (Okay, Facebook, Twitter and Spotify. I’m human.) and write my ideas by hand in an A4 spiral bound notebook. This is also a really good excuse to treat myself to some of the pretty stationary from Wilko’s. It makes me slow down and consider the direction of the story and gives me an instant hard copy safe from glitches and fatal errors which can so easily wipe your work from the face of the earth.

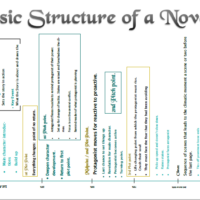

One tool you do need is an understanding of dramatic structure. No matter how exciting your story’s basic idea, an incomplete view of how a story is put together will take you round in circles. You might think you are being rebellious and daring by refusing to adhere to a ‘formula’, but if you don’t know how a story structure works, what are your rebelling from? Even the impressionist painters of the 19th century knew how to ‘do it properly’ before they started playing with techniques and new styles. Read books, take free courses, test yourself. Do whatever you need to in order to understand this. A copy of the Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms is an invaluable source in this learning process.

Larry Brooks describes six ‘core-competencies’ within the craft of storytelling. One of these is structure. The others are

- Character

- Theme

- Scene

- Execution, and

- Voice.

Your job as a writer is to get good enough at one of these that you stand-out in a crowd of thousands with the same skill-set as you.

No mean feat and I applaud you for taking on the challenge. Here’s the bad news: It’s going to take practice and planning, work, and possibly years, to achieve this. There is no short cut.