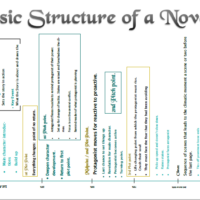

Basic novel structure

With NaNoWriMo fast approaching, there will be many writers embarking on a new writing project this November. With this in mind, I have put this PDF together to serve as a basic guide for outlining. This has been built from a handwritten version compiled by Nichole McGhie from thexcitedwriter.com and is based on K. M.Weiland’s Outlining your Novel which is worth a read on its own. The poster is designed to print out onto 2 A4 sheets of paper and still be readable so newbie writers will be able to pin it up in front of them. I recommend you do. While the information in this poster is by no means exhaustive, it does offer a sound framework.

From my own experience of NaNoWriMo, now is the time to get outlining and thinking about tour plot and characters. I will stress here that I didn’t actually finish my first draft until May (oops) but I am now in the final stages and hope to complete my final round of editing on time to get it formatted and then self-publish in November. The reason I didn’t finish on time is that I started without a complete outline and then got stuck at the midpoint while I worked out what should happen. This is not an experience I wish to repeat and it is also why I strongly advise my clients to prepare an outline before they start. Having an easy means to keep track of your plot, sub-plots and character development will save you a massive amount of time and stress in the long run. It is also the best way to

Having an easy means to keep track of your plot, sub-plots and character development will save you a massive amount of time and stress in the long run. It is also the best way to avoid a huge amount of rewriting – not to mention disappointment – after you get it back from your editor, having already given them a migraine. If you want your editor to love you, then you MUST outline but I wanted this to be more of a ‘how’ post than a ‘do this and this is why post’. Most seasoned writers by now understand the importance of planning, especially if they write in series. I’m addressing the novices and the people who are planning to dip their toes into creative writing for the first time so below are a few more pointers you should be thinking about while writing and planning.

Dos

- Think carefully about your POV. Does it work for the genre?

- Is your story more heavily weighted in favour of plot or character? Ideally, This should ideally be a 50/50 mix of both but some genres can cope with more than one than the other.

- Is the conflict proportionate? A story without a problem to solve isn’t a story and that’s basically what is meant by conflict. This can be internal or external but there must be an obstacle between the character and where they want to be and it has to be believable. That’s about the crux of it. Think about how often you have put a book down because it wasn’t grabbing you. Ever thought about why? Most of the time I have found it’s because the protagonist’s life is either too easy or too hard; everyone loves them and everything happens their way or, the less frequent, a complete train wreck of a character whose problems are insurmountable and there is no hope of them ever overcoming them. The protagonist doesn’t have to solve the problem, and sometimes that can make for a more interesting story, but there still has to be a possibility that they will overcome that obstacle. Do they realise why they don’t manage their task?

- Consider plot progression as well as pace, Do the events in your plot occur within in a logical progression? They need to present a sequence of events leading clearly from the beginning (the catalyst) to the conclusion. A series of seemingly unconnected events will only bore your readers. In other words, if a character is doing something, they need to have a good reason to be doing it.

- Use an editor. Spellcheck can’t correct structural issues or dialogue.

Don’ts

- Use the act of writing to show off your vocabulary and hope it’ll cover up the fact that there is nothing happening. Really, don’t. A strong story, with the action at the right points, can support some flowery Hardyesque prose. A weak one? Well, you might as well have rewritten the Mayor of Casterbridge (that book is a sore point with me). You will also give your editor a headache. A good one will spot this a mile away and should call you up on it.

- Don’t describe what one of your cast is about to say and then put it into dialogue. If you are in doubt about what someone has just said, read it aloud. Would that sound awkward coming out of someone’s mouth?

- Don’t try to outline every last detail. You need to leave some room for flow.

- Don’t try to edit as you write. You will get nowhere quickly. Get that first draft down then go back over it as a read-through before touching anything. Make a note of your plot points, as well as where they are, and compare them with your outline. This should help to identify any weak areas to fix in your self-edit before sending it to an editor.

- Do not send your unedited first draft to an editor.