by Anna Johnstone | Jan 22, 2019 | Blog

Good morning!

Welcome to another Tuesday round-up. This week we have another great podcast from The Creative Penn (okay, total fangirl) discussing running a one-person business, the Kobo Writing Life talks about podcasting as content marketing., and the Writership podcast discusses scene and story resolutions. In articles, we have two very informative articles on shrinking author incomes, and another on corporate censorship and their unchecked power. I’ve not had time to check out videos for this week’s round-up, but hopefully, I’ll be able to gather a few links for next week.

Happy reading!

The Disastrous Decline in Author Incomes Isn’t Just Amazon’s Fault

The bookselling behemoth is making life harder for writers, but so is the public perception that art doesn’t need to be paid for.

Publisher's Weekly | Breaking Down Financial Woes for Writers

In an effort to gather as much information as possible about how much authors earned in 2017, the Authors Guild conducted its largest income survey ever last summer, reaching beyond the guild’s own members to include 14 other writing and publishing organizations. In all, the survey drew 5,067 responses from authors published by traditional publishers and from hybrid and self-published authors as well.

Corporate Censorship Is a Serious, and Mostly Invisible, Threat to Publishing

When state or civil authorities blacklist books, the act is correctly labeled censorship. But what is the word when corporations order their subsidiaries to snuff out information?

The Creative Penn | How To Be A Successful Company Of One With Paul Jarvis

What if you could scale your revenue without growing your expenses? What if you could make a living with your writing but still remain alone in your writing room? I discuss these questions and more today with Paul Jarvis.

In the intro, I talk about second-hand book sales [Dean Wesley Smith], how the death of poet Mary Oliver can help deepen our writing [listen to her on the On Being Podcast], why ‘sparking joy‘ is so important (referencing Marie Kondo on Netflix), plus the Kickstarter for Intellectual Property Tracking.

Kobo Writing Life | Ep 133 – Let’s Talk Podcasting with Amanda Cupido

n this week’s episode, Cristina sits down with author and podcast producer Amanda Cupido to talk about her book Let’s Talk Podcasting: The Essential Guide to Doing it Right. Amanda talks about how she got into podcasts, the difference between podcasts and older media such as radio, and she discusses the underrepresented voices in the podcasting community. Amanda also shares her tips for starting your own podcast and the most common roadblock that aspiring podcasters encounter.

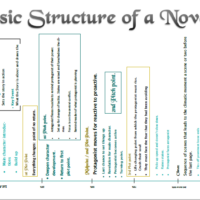

Writership Podcast | Ep. 136: Resolutions

We all have some idea of what a resolution is, but what are these scene and story-enders meant to do? In this episode, I explore scene and story resolutions in the context of C. Gabriel Wright’s LBGTQ love story, “Someone.” The editorial mission encourages you to collect resolutions by reading and watching stories—and from your own life.

![How to be a good client.]()

by | Mar 26, 2017 | Advice, Blog

We’ve all heard of that one person who demands more from a service than is strictly reasonable, haven’t we? They want the dry cleaner to somehow get the turmeric stains off of the front of their favourite top and then scream blue murder if they – unsurprisingly – fail. They expect freebies, discounts, and are rude to waiters. They delay paying a bill for something because they’d rather go down the pub. They’d even go so far as to make a spurious complaint on the off-chance that they could save a few quid, never mind the effect that complaint could have on another person. Okay. These are extreme examples. The point is that while we expect to get our money’s worth out of a service, a healthy business relationship is a two-way street. In light of this, here are a few things to bear in mind in order to not be that customer.

Always prepare a brief.

We love these. These tell us exactly what is expected of us and enable us to realistically price and plan your project. A brief to an editor should include the following information.

- The title of the work and the author’s name and contact details.

- How many files are involved and what they include.

- The nature of the work. Is it a novel, an essay for assessment, an article for a magazine etc.? This helps us assess if we have the necessary skills to complete your project. Some editors specialise in fiction in a particular genre so sending them your dissertation on the history of the paperclip (gripping material) would not do you a lot of good.

- The deadline and when you expect the project to begin. This editor might not be available at the time you need them. If you ask, they might be able to point you in the direction of someone who is not only available but shares your obsession with stationery.

- The length of the document. This will affect the pricing of the document. Your editor needs to factor their time into the equation.

- Is it a blind edit? If the document has undergone editing prior to your project, you may want to send the original as well as other documents so that this editor can see what changes have already been made. You don’t want them undoing the work of another. It’s a waste of their time and yours.

- The style guide or house style you are working from. Send them a copy so they can familiarise themselves before starting work.

- The level of intervention expected. Don’t be the client that asks for a copy edit but expects the whole thing to be rewritten. This part of the brief allows the editor to clarify which parts are part of the normal service and which bits are extras. You will be expected to either sacrifice extras or pay for them. Similarly, you might only want to check for spelling, grammar and typos.

Your editor has many talents, but mind reading is not one of them. The brief above is the bare minimum of the information you should expect to provide. Being clear from the beginning will help avoid any nasty surprises later on. It will save you both time,

The price may be negotiable but an agreement is an agreement.

Many editors now will issue a service agreement relating to the final negotiated terms of payment. These include the services expected, sometimes in great detail, so be sure to read them thoroughly before sign anything. It also includes the rate that you have agreed to. This agreement stage protects you as much as the editor but while it constitutes a promise to carry out x, y, z, it also constitutes a promise from you to treat the service provider fairly.

A service agreement will, at the very least, include the rate that you have agreed to pay, the services to be carried out, deadlines, and the dates by which it is to be paid. You might have arranged an instalment plan. If so, you have a responsibility to make these scheduled payments at the agreed time. It will likely list any penalties and consequences for not meeting your side, as well as what they are prepared to do in the event that they fail to fulfil their end. If you do not feel these are fair then you should not sign the agreement. Attempt to negociate terms but be fair. You cannot expect them to remove anything that protects them.

Asking for extras mid-project is another danger area. For instance, if you went to a local store to collect and pay for your paperclip order but, on the way, decided you wanted bulldog clips instead, you would expect to pay the bulldog clip price, would you not? The rule is the same for services. If you want extra, this may often mean amending and signing the service agreement to reflect the changes. You can be a good client by

- Asking if it is feasible to extend the length of the project. Your editor may not have the time. Some of us work on more than one project at once while others prefer to concentrate on one project at a time. We all work differently so you should double check that we are available before giving us extra work.

- Ask how much extra it will cost. If you went to a local store to collect and pay for your paperclip order but, on the way, decided you wanted bulldog clips instead, you would expect to pay the bulldog clip price, wouldn’t you? The same applies to services. Similarly, if you found that you had left something out of your brief, and it hasn’t been done, you would not complain that the editor did not fulfil your brief.

- Paying as promised and on time.

Trust

This works on both sides. You need to trust that your editor knows what they are doing and that they can deliver the service to the promised standard. They need to trust that you will uphold your end of the bargain. No matter who much you like an editor, if they feel that you have acted unfairly, they may decide that the stress of working with you is not worth the price.

You chose your editor because they possess a skill set that you do not. For this reason, alone you should listen to them. Give them the freedom to keep their promises to you. Editing is a collaborative process which takes both time and care. If they come to you with a query, answer it promptly and politely. It is true that anybody can call themselves an editor, and unfortunately there are cowboys and charlatans in every walk of life, but the good ones know their craft. Treasure them. Many are published authors in their own right so have experience from both sides of the relationship and empathise with your anxiety. They also take pride in their work and want to help you make the best of your work. It’s not just about making money.

Professional pride

Like other services, our living relies upon our reputations. There is a fine balance between personal opinion and the decisions formed by experience and skill. If your editor feels they are unable to point out flaws in your writing, due to the reaction it might induce, they will not be working to your best advantage. You want your editor to pick up problems and bad habits. It’s how you will learn to be a better writer. So while an editor might exceed their remit in some cases, remember they are doing the job to the level that they would eexpectto receive it.

Back to the dissertation analogy here. Say you handed them your brief to check spelling and punctuation only, but the editor noticed that your use of paperclip vs. paper-clip was inconsistent, but because they had not raised the issue or highlighted them, you were marked down by your tutor. And what if the reason they had not mentioned anything is becasue you had refused to accept input over the wording. This would not be what the editor would regard as a successful outcome even if they had fulfilled the terms of the brief to the lettter. This can be avoided by

- Being flexible with your brief. If you have left something off and the editor raises the issue, it is usually because some part of your writing has raised a concern and they could not, in good conscience return the editied work without raisning the issue. This is a good thing.

- Ensuring your brief includes everything you want from the service. It is also way the pre-project discussions are so important.

Reasonable deadlines

It doesn’t matter how fast someone reads...Scratch that. It matters a lot.

Proofreading, in particular, means slowing… right… down… and taking in every word carefully. It means looking for extra tall lettters hidden with others, because the human eye is a lazy beastie and will assume that what it sees is what is really there. Reading a two hundred page novel might be possible in two or three days, but editing is not the same as reading for pleasure. Often, it means checking that all captions match images and bibliography formats are correct, looking for double spacing, transpositions, or repeated text. In other words, it means doing what the spell-checker can’t do; apply common sense. This is also why you shouldn’t just forgo editors and rely on the spell check. The spell check can’t find plot holes. It is vital that you apply common sense and allow adequate time for the work to be carried out. A betaread of a 85k word novel could easily take two weeks due to the level of care needed in the reading.

Leave fair and honest feedback; spread the word

If you are happy with the service you have recieved then say so. Frequently. Recommend them to colleagues and friends. Way back before the internet, businesses lived and died on their reputations. Today, this is even mor the case. The rise of social media means that the lack of pressence and reviews is almost as bad as negative reviews. It tells future clients that this person cannot deliver what they promise. It’s like the boss who ‘loves’ you right up until you leave, then refuses to give you a reference. Reviews are the references of the information age. Use them. Tell the world you love your editor and why.

The other thing not to do is to leave vaugue feedback, or comments which contradict your repsonses to the editor. The feedback is not the place to bring up new problems. It is the place to tell people how well your editor did their job including dealing with a misunderstanding over style. Your editor relies on feedback to not only gauge reach and reception, but to iprove their service. It is important they these be honest. A dishonest negative review can do someone real harm, they are not funny or ethical. If your editor has failed to meet a deadline or fulfil their side of the agreement, AND THEN failed to deal with the situation adequately, then by all means take to their facebook page and lambast away. At least initially, you should deal with greivances calmly and in private.