Dangers of dithering

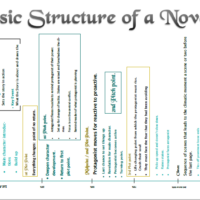

Last week I talked about unnecessary content and scenes which do not drive your story ahead. This week I am going to continue on that theme because I cannot stress enough the importance of clarity. While a good structure is vital, don’t be in too much of a hurry, or try to race through to the end. Writing is a hike, not a 100-yard dash. Hiking means being able to take in the surroundings, enjoy the autumn colours, spot wildlife, and properly stretch your creative legs. Doing it at a flat-out run means indistinct settings and unclear description. By trying to go too fast, you risk missing out details which help to set the scene. It will not make your reader more alert but lead them to ask the wrong questions about your narrative. In turn, being vague or indistinct means you are leading the readers’ attention away from what they need to know about the story, and missing out on an opportunity to build some depth into your characters through observation of their reactions.

Look at the following examples from K.Weiland’s ‘Most common Mistakes’ post from 2011:

- Maddock looked at the wall, which seemed to be smeared with spaghetti sauce.

- The bomb fell approximately ten or twelve feet away from me.

- Elle was about forty-five minutes late for her dentist appointment when a cop pulled her over, apparently for speeding.

- Mark’s figures revealed that the addition to the house would take up roughly fifty square feet.

Do any of them really help you to set the scene or give the reader a feeling that they need to know this? Nor me. It makes me think this is just filler. Why is the author wasting my time in telling me this? Take out the supposition and the approximation, then we know that the information is important and we will probably need to remember it later. Being unsure of the measurement of the house could prove very expensive, but being definite about it has us asking, why he wants to extend? Is Mark trying to hide something? Is he building a secret den? We know when something comes out flat. It feels trite or contrived; as if it could really be done away with. Being vague has the same effect. If that information is important then the ‘seemed to’, estimations, and approximations need to go. Your author voice will come through the stronger for it.

Sometimes, however, you will need to guide the reader or drop hints about the action or something the main character has observed. There are ways to do this but many of them are wrong. K. Weiland has again offered us a handy list of words to avoid:

- Seem

- Approximately

- About

- Appear

- Look as if

- Roughly

- More or less

- Give or take

- Almost

- Nearly

Persuasive, and evocative descriptions are a vital part of any narrative. Being vague is apologising to the reader for knowing more than they do, or trying to point something out and trying not to sound too clever about it. Stop apologising. Your job is to direct the gaze of your readers. Do not hesitate to give a full sensory experience. In a crime scene, for instance, your main character would be looking for clues. Your reader will be asking what did the air smell of (decay?) or was there a lot of blood or how far the deceased’s head had landed from their body (have someone use a tape measure). ‘Seemed to’ writing will only serve to diminish their experience, as well as rob at least two people of the experience of imagining it. This is not to say that you cannot use metaphor to transmit your meaning, but be cautious. There is the risk that you, as a new writer, will be tempted to hold your reader’s hand and explain them. Don’t. If you have got it right, the reader will understand it. Likewise, if you show your reader what is there, then they will see it.

Sweeping statements and generalisation is another form of dithering to look out for, and eliminate. You don’t need to make sure the reader ‘gets it’. Long winded justifications of your action won’t achieve this either. By going around the houses in order to set the scene you risk boring your audience with the minutiae and they will miss things they are meant to see. It also hints that you are unconvinced by your own story. The message here is to slow down. Be bold enough to say precisely what you mean and what you want your readers to see. Your readers will thank you for it.